mHealth (mobile health): The use of mobile and wireless devices to improve health outcomes, healthcare services and health research.

The FDA recently issued final guidance on the regulation of mHealth apps, and we wanted to take a closer look at what it all means – or could mean in the future – especially for childhood cancer families.

The FDA recently issued final guidance on the regulation of mHealth apps, and we wanted to take a closer look at what it all means – or could mean in the future – especially for childhood cancer families.

According to a recent report, there are over 40,000 health-related apps available on iTunes alone, and that number is sure to keep growing. By 2015, it’s estimated that more than 500 million smartphone users will be using a healthcare app. The vast majority of apps available for your iPhone or Android, however, aren’t the type that fall under FDA regulation. The FDA took a “tailored approach” to this regulation, deciding only to focus on regulating apps that could actually pose significant risk if they don’t work correctly. According to the final guidance, the mHealth apps that require FDA approval are those that function as a mobile medical device or an accessory to a medical device.

What does that mean? If the app is intended to diagnose a disease, help treat a disease, or prevent a disease, then it’s considered a medical device and it may require FDA approval to ensure safety and efficacy. Clear-cut examples are an iPhone attachment that detects abnormal heart rhythms or using a smartphone’s camera to send images to a health professional for the purpose of diagnosis. There are now more than 100 of these apps that have been registered with or cleared by the FDA. The app description will likely include something like “FDA-cleared” if it falls into this category.

If the app is providing general education (like WebMD) or helps you track diet or exercise for your own information, then it does not require regulation. But there’s a lot of gray area between the apps that clearly require regulation and those that clearly don’t, and those areas have been the most hotly debated in the area of mHealth.

The new guidelines helps define some of those gray areas by outlining the type of apps that the FDA technically could regulate but are unlikely to because they are in a lower-risk category. Here are a few examples of these “enforcement discretion” apps that could be of interest to families of children with cancer:

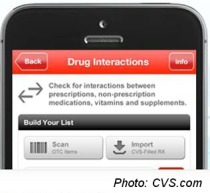

Drug Interaction: CVS’s mobile app recently added a component where users can scan barcodes of over-the-counter medicines to ensure that multiple drugs are safe to take concurrently. The FDA guidelines do stipulate that such mobile apps must provide citations from literature to any medical claims the app makes.

Drug Interaction: CVS’s mobile app recently added a component where users can scan barcodes of over-the-counter medicines to ensure that multiple drugs are safe to take concurrently. The FDA guidelines do stipulate that such mobile apps must provide citations from literature to any medical claims the app makes.

- Recordings of Doctor-Patient Conversations: This refers to an app that records doctor-patient meetings and sends them to the patient or family to listen to after the visit. We can imagine how helpful this type of app would be to parents facing their first, terrifying visit with the pediatric oncologist and finding all the details too overwhelming to remember – but too important to forget.

- Nurse Hotlines: This could include hospital-branded apps that feature a contact section with access to nurses who can provide guidance. It’s someone who can talk you through the middle-of-the-night questions: Should we go to the ER now, or can it wait until morning?

- Medication Reminders: Mobile apps that send user-set alarms and notifications when it’s time to take the next pill.

Have you found any mobile apps that help you provide care for your child? Let us know in the comments what’s worked for you and your family.

Pingback: [Reblog] Who is making your medical app? « Health and Medical News and Resources